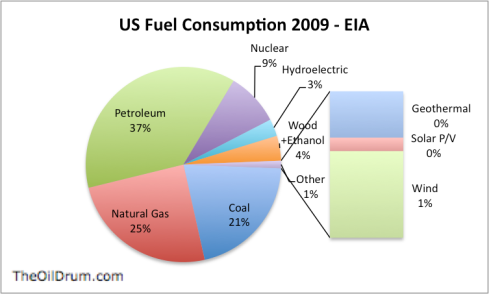

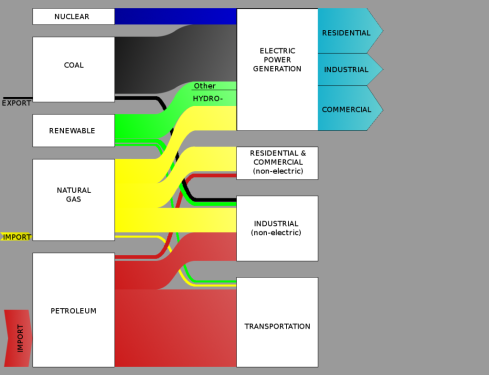

Here are two views of energy consumption in the US economy. You could consider these as a snapshot of the economy in terms of the energy sources that make it function:

and

Before the credit crunch which marked the beginning of the Great Recession in 2008, growth in the US economy meant making, selling and using more conventional cars and trucks and planes; building more roads and subdivisions; shipping more products from all around the world to everywhere in the world; vacationing at more distant and exotic resorts; and burning more fossil fuels for every aspect of growth. The economy that both major political parties are trying to revive gets roughly 85% of its physical energy from fossil fuels and 96% of its transportation energy from oil.

Cars, trucks, trains, planes and ships all run on fuels that are made from oil. Their engines are built to run on specific kinds of fuel, and each engine will run only on the specific kind of fuel for which it is built. Ongoing depletion of the world’s oil fields – peak oil – guarantees we will not have more cheap fuel available in the future. We will have less, and what is available will not be cheap.

The United States passed its peak of national oil production in 1970. Since then the amount of oil produced in this country has declined to about half of what it was in 1970. Development of new oil discovered in Alaska and in the Gulf of Mexico only served to slow the rate of decline. Development of secondary and tertiary methods of recovery from old oil fields has also slowed the rate of decline, but all the new technologies together have been unable to reverse the trend of decline.

The United States has for some decades been able to compensate for declining domestic production of oil by importing more and more from the rest of the world, at least until recently. Now, the world as a whole is near and possibly past its peak of oil production. That’s the basic reason the price of oil went from around $20 per barrel in 2000 to $147 per barrel in the middle of 2008. Oil at that price made further growth of this economy impossible.

Onset of the Great Recession knocked the price of oil temporarily down to the $32 per barrel range. Already in April of 2011 the price per 42-gallon barrel is over $100. This price level is threatening to start us on the second dip in what may prove to be the Greater Depression.

Economists and politicians have all kinds of stories to tell about why the price is so high – speculators, tight-fisted Arab and South American nations that want to destroy the United States, wrong-headed policies of the Federal Reserve that destroy the value of the American dollar, stupid environmental regulations that have prevented drilling, and so on.

All these stories distract attention from the simplest logical explanation – the laws of supply and demand work. Shortage of supply drives up prices until some demand is destroyed. The economic crisis of 2008 was demand destruction in wholesale lots.

If it’s not possible to increase the quantity of fuel available for transportation; if that quantity continues to decline globally; then all the plans for growing this economy will instead end with contraction and more demand destruction. There is no political solution, no military solution, no financial solution, and no technical solution that will create more oil in fields that have been sucked dry.

Transportation that depends on plenty of cheap oil means we are going to be living with repeated contractions of the oil economy for the foreseeable future. We had better learn how to adapt to it.

Of course, if oil is getting to scarce and too expensive, then we will seek some other source of energy for our industrial transportation. Scientists and engineers have been looking intensively since the first oil shocks of the the 1970s. The short story is that all alternative sources for transportation energy are even more expensive and more limited than oil.

The processes involved in making alternative liquid fuels that could go into our existing vehicles take considerably more energy than making fuels from conventional oil. The net energy of biomass, coal-to-liquid and gas-to-liquid fuels is too low for economical manufacture. In addition, there is not enough farmland in the United States to replace the oil we import with biomass, even if we don’t use any of the land for growing food.

Clearly in the real world, we won’t entirely stop growing food to produce biomass for fuels. We will never come close to replacing the amount of oil we import with biofuels.

Replacing all our vehicles with ones that will run on something other than liquid fuels – natural gas, electricity and hydrogen are the main candidates for something else – will take decades, if it can be done at all. After decades of attempted development already behind us, the vehicles are still fantastically expensive to manufacture or the infrastructure to fuel them does not exist, or both.

To revive the pre-2008 economy in the immediate future, more oil would have to be available. Instead, progressively less will be available. To repeat: There is no technical, political, financial or military solution that will make more oil available. Therefore, the corporate, global, industrial economy that we have inherited will not resume growth in the foreseeable future. It will continue to contract.

Our economy has in some ways been contracting for decades. The peak of annual per capita energy use in the United States, at 359 million BTU was reached in 1978-79. Since then, it has declined in a bumpy fashion to 308 million BTU per capita in 2009. This is shown clearly on the first page of the Energy Information Administration’s “Energy Perspectives” document:

http://www.eia.gov/emeu/aer/pdf/perspectives_2009.pdf

Since roughly 1980 real wages in the USA have been flat or declining. For the last several decades, there has been no sustainable economic growth. There has instead been a significant transfer of wealth to the richest 1% or so of society. The statistics showing growth in recent decades indicate increased wealth for a few with stagnation or loss for the rest of us, not an increase in general prosperity. Now that peak oil is having such a powerful effect it can’t be hidden or denied, it might be time for us to admit the long decline of industrial society has begun.

In the midst of this decline, and because of this decline, it will be necessary to create multiple localized economies that can work without cheap fossil fuel energy. That’s the basic idea of the Transition Town movement. We don’t expect a program for “green jobs” to revive the economy. We don’t expect real estate values to recover. We don’t expect industrial agriculture, which burns 10 calories of fossil fuel energy for every calorie of food brought to market, to continue to feed us. We need to transition from a high-energy low employment society to a low-energy high employment one.

If we are right, then it makes sense to develop local food production. It maks sense to develop ways of using less energy. It makes sense to do everything else that will allow us to live well without depending on fossil fuels. That’s going to take individual and community adaptation. We should not expect to be finished in a year or two.

Suppose twenty years down the road we are proved wrong. Suppose we have worked on a transition made unnecessary by discovery of a new miracle source of abundant clean energy. We will have saved money, gotten more exercise, spent more time outdoors, eaten a healthier diet and gotten to know our neighbors better. It’s not a terrible result.

Then suppose we are proved right. Starting earlier on the transition to a low-energy localized economy may make the difference between surviving communities and failed ones. Being stuck in a failed community, such as some of the ruined neighborhoods in Detroit and elsewhere, is a terrible result. We don’t want Ferndale – or Hazel Park or Royal Oak or Oak Park or Palmer Park – to become failed communities.

The basic idea is, the type and quantity of energy to keep our industrial society functioning no longer exists. The cheap and plentiful oil has been burned up, and it can’t be unburned. It’s a shocking idea that goes against all the commercial and political advertising with which we are bombarded every day. It’s hard to digest.

People have actually become dizzy, sick and depressed when they figure out this is not just an old George Carlin comedy routine good for a few laughs, or something else they can easily dismiss. It’s far easier and more comfortable to believe that technology will save us or alternatively, that Armageddon is inevitable anyway. With either type of belief, we don’t have to do anything about such a disturbing idea.

The Transition Towns movement consists of people who have digested this disturbing idea, and are testing how to live with it. We may have to try a dozen things to discover a couple that work well in this community. We’ll have to get hundreds of people participating, and not just in occasional discussions, before we can say we are creating a transition community here. We’ll continue discussion of these issues with our video series and at our pot luck/business meetings.

John Kenneth Gailbraith, in his 1975 book “Money, Whence It Came, Where It Went,” on page 103 said:

“Where economic misfortune is concerned, a word on nomenclature is necessary. … During the last century and until 1907, the United States had panics, and that, unabashedly, is what they were called. But, by 1907, language was becoming, like so much else, the servant of economic interest. To minimize the shock to confidence, businessmen and bankers had started to explain that any current economic setback was not really a panic, only a crisis. They were undeterred by the use of this term in a much more ominous context – that of the ultimate capitalist crisis – by Marx. By the 1920s, however, the word crisis had also acquired the fearsome connotation of the event it described. Accordingly, men offered reassurance by explaining that it was not a crisis, only a depression. A very soft word. Then the Great Depression associated the most frightful of economic misfortunes with that term, and economic semanticists now explained that no depression was in prospect, at most only a recession. In the 1950s, when there was a modest setback, economists and public officials were united in denying that it was a recession – only a sidewise movement or a rolling readjustment. Mr. Herbert Stein, the amiable man whose difficult honor it was to serve as the economic voice of Richard Nixon, would have referred to the panic of 1893 as a growth correction.”

You may have heard that a depression is defined as any economic downturn where real Gross Domestic Product (GDP) declines by more than 10 percent. A recession would then be an economic downturn that is less severe. This and other conflicting definitions sometimes quoted in newspapers and news programs have been made up by some economists but are not generally agreed on.

In any case, the measurement of GDP is not a reliable number. The method of measuring GDP includes “adjustments” to make the dollar figure larger than it would be if only actual transactions were counted. Similarly, measurement of inflation by the Consumer Price Index has been tuned to make the number as small as possible, to minimize Social Security payments and cost of living adjustments in contracts. Measurement of the rate of unemployment has been so massaged that recently the reported rate has dropped even while the more straightforward rate of participation in the labor force has also dropped.

There’s a detailed explanation of how and why economic statistics have been cooked to make the economy look as good as possible at John Willaims’ website, http://www.shadowstats.com/. The gist of it is, if the numbers look good, then the politicians in charge appear to be competent. Even with the best-cooked numbers, official statistics have not made the people in charge look competent for some time now.

Harry S. Truman is reported to have said, “It’s a recession when your neighbor loses his job; it’s a depression when you lose your own.” This is at least as good a definition of recession and depression as those made up by economists. We will experience plenty of economic downturn as fossil fuels fail us. This economy is not going to grow without plenty of cheap energy. Whether we call it a multi-dip recession or the Greater Depression or (as James Kunstler would have it) the Long Emergency does not matter much.

The important thing is not picking the best name, but understanding why the empire is declining (another popular expression) and what we can do to survive the experience. Call it a crisis. Call it a Great Turning. Call it whatever helps you cope.

We call it energy descent, because that might help us come up with an energy descent action plan.

Leave a comment

Comments feed for this article